MARKET STREET GEEZERS

by

Andy Winnegar Sr

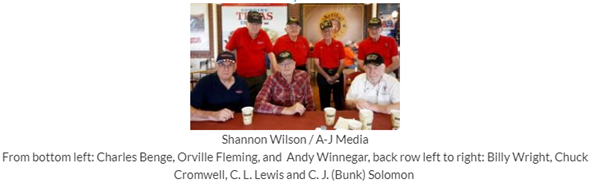

In July 2014, C. L. Lewis mentioned to his daughter Vicki Hensley that he missed the camaraderie of the WWII veterans of the 2012 South Plains Honor Flight to Washington D.C.

Hensley, who worked at United Supermarkets’ Market Street at 50th Street and Indiana Avenue, suggested he start a weekly coffee klatch by phoning some of the vets to see if they would be interested.

A few of the WWII veterans did respond and called their friends, some invited Korean and Vietnam Honor Flight veterans and the members expanded. They agreed to meet on Monday mornings at 9:30 wearing a veterans identifying cap of some sort, no other requirements.

They do not have a Charter, membership dues or membership list. The member who does their Facebook page gave them the name of Market Street Geezers. They are Army, Navy, and Marine: their only Coast Guard veteran passed-away a year or more ago.

They are there for the conversation which is mostly about everyday life and seldom about the war but they are patriots and it will show even if the subject is how to install lawn sprinklers or what fraction of an inch of rain fell. There will be several conversations going on at the same time, possibly because a Geezers hearing range is measured in feet, easily verified by the number of hearing aids. Hearing aids themselves are often a subject. The number of days you can get on a battery is kind of like how many miles your new car gets per gallon.

The present senior member is C. J. “Bunk” Solomon who will be 95 in August, and the only ex-POW. They served on air, sea and land, some serving a few years and others over thirty years. Geezers are decorated veterans who served in bloody combat and others never left the States but at Monday morning coffee they are all just Market Street Geezers.

If you are in the vicinity of 50th St. and Indiana you could stop in the Market Street Coffee Shop, (now Starbucks Coffee Shop) and if it is around 9:30 Monday morning you will see them in a niche on the east side carrying on lively conversations. Thank them for their service and look at their expressions, if you love your country, you will feel a lump in your throat and these nonagenarians will make you feel years younger. If you would like pictures of some of “The Greatest Generation”, pictures are allowed, but please ask permission first.

South Plains Honor Flight veterans of all flights 2012 to 2017 are welcome. There are no dues and if you feel it isn’t for you, you have no obligation to return. As of now fifty percent of the original 2012 Honor Flight has passed on and time has not been good to the Geezers either. Although they have had only one death many have become homebound or gone into nursing homes.

See them on the internet!

The A-J Remembers: C.L. Lewis patrolled Berlin after World War II

Andy Winnegar Sr

806-790-3871

awinnegar@gmail.com

*The articles below were taken from “The A-J Remembers” and written by Ray Westbrook-AJ/MEDIA

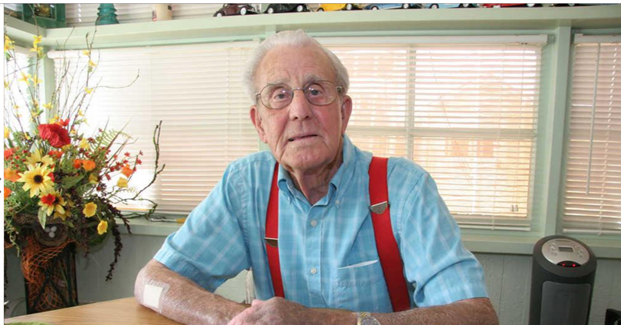

C.L. Lewis may have seen the virtual start of the cold war while he was serving in the occupation forces in Berlin shortly after World War II.

And it wasn’t a confrontation between communism and democracy, it was an issue involving certain soldierly arts.

“We had more trouble with the Russians than we did with anybody,” Lewis remembers.

There was a Russian zone of course, and it was clearly marked with a sign that proclaimed, “Entering Russian Sector.”

“They weren’t smart, but they knew the Americans had cigarettes and whiskey. I don’t know how they found out about it, but they did, some way,” Lewis said.

“Berlin all looked the same, and the streets didn’t mean much to you – you kind of went by landmarks in that place,” he remembers.

“The Russians would come out and take that sign down and watch and let an American soldier come walking into there – and they would kidnap him, is what they did.

“Then they would notify them that they had an American over there in the Russian zone, and they would trade him for cigarettes and whiskey. They did it on purpose. They took the sign down that said ‘Entering Russian Sector.’ ”

Lewis had grown up in Missouri, and was fortunate to have been taken into the Army on June 1, 1944. He was too early for the D-Day invasion, and was in a replacement center until after the battle of the Bulge.

Entering service

He remembers the military draft, which he terms “capture,” this way: “You go from being an old farm boy to military service, and it’s a completely different world.”

The Army quickly took possession of him.

“I tell people that you just can’t imagine an old poor country boy being put in military service. They put me on a bus about 9 o’clock one morning and drove to Fort Riley, Kansas. Got off there about midnight, hadn’t had anything to eat that day, and they told us we were going to get something to eat. Well, we got to bed about midnight.

“They woke me up at 4 that morning, took me over to the mess hall, and said, ‘You’re going to work in the cooking department.’ I said, ‘I’m not a cook.’ They said, ‘That doesn’t matter, we’ll show you how to cook.’ ”

He relates his experience with cooking this way:

“I cooked spaghetti for 12 hours. They had this big old tank thing, hooked up there, and they showed how to do all the stuff. You pick that spaghetti up and put it on your shoulder and walk up this ladder and drop it in there. Once it cooked the distance – they had a clock there, and you set it, and the time came to shut it off – then, you got this stuff and put it in pans about that long and about that wide and about that deep. And that was all day long.”

Was that after basic training?

“No, that was before I was ever sworn in. They put me right to work, right after I was captured, about the first of June. I mean, I hadn’t even been sworn in.

“We couldn’t do anything about it. They had us and we were there.”

Off to Europe

Following basic training, Lewis was shipped to Europe, and not told where they were landing.

“I know we didn’t go a hundred yards before we were walking in mud three or four inches deep. Then, they got us on a train and took us to a town and we went into what they call a replacement center. They would come in and get a few and they would leave. I got missed an awful lot, and I was glad.

“The last place I went to was Marburg, Germany. That was the last place I went to, to the replacement center there. Then, when the war ended in Europe, we went into Berlin. I was on the occupation force there in Berlin for over two years.”

He remembers, “The Germans were scared of us, but they liked us.”

Search and patrol

For the first two months after the war ended, they were sent to search for weapons. “You know, you go into somebody’s house, and you have to open the drawers and go through them. I think they were afraid we were going to do something to them.”

He remembers that after the weapons search ended, they patrolled the city in an armored car. “We were kind of like policemen. We had to carry a loaded pistol while we were there, and in the armored car I had a Thompson submachine gun.”

He remembers the city had been torn to pieces by bombing, and there was an area that particularly caught his attention. “I remember there was an area over there – I imagine it was probably four square miles, maybe two or three square miles but it seemed like four square miles. And there wasn’t a building standing in the whole thing except right out in the dead middle of it. It was a little building, 20 feet wide, one story high, glass windows still in it – it was F.W. Woolworth.”

Brick by brick

Lewis also saw the sobering site of German women chipping mortar off bricks and stacking the bricks in neat stacks to be used in rebuilding.

“The first year I was in Berlin, I don’t know how the people were getting food. There were no grocery stores, no place to get food, though there could have been and we didn’t know about it.”

He does remember going into the Russian zone two or three times, but never on foot, always in the armored car.

“They didn’t catch me, I stayed away from those places. We had a lot of trouble with them trying to steal food and stuff out of railroad cars we had.”

He remembers, “We saw Hitler’s bunker. They wouldn’t let us go into it, it was all underground in concrete.”

Although the patrolling work went on perpetually, much of it was routine for Lewis.

“We were in charge of everything in Berlin – whatever we said, that’s the way it had to go.”

He remembers escorting American troops or equipment that was coming into Berlin.

“We would do that once or twice every month, but the rest of the time we just patrolled the streets, minded our own business, and tried to stay out of the Russian zone.”

As for the cold war, he knows how it began:

“Yeah, they started it then.”

ray.westbrook@lubbockonline.com

‒ 766-8711

Follow Ray on Twitter

Westbrook: Chuck Cromwell remembers World War II era

Chuck Cromwell, who was living in Memphis, Tennessee, in December 1941, can recall vividly when he heard Japan had attacked Pearl Harbor.

“I was 16. What I remember more than anything was walking back home from the street car line, and a neighbor across the street came out on her front porch and said that Pearl Harbor had been bombed.”

That sounded serious, so he asked the neighbor to say it again.

“Pearl Harbor’s been bombed.”

“And I said, ‘Where in the world is that?’ ”

He remembers, “I went in the house and found my dad already had his head glued in that Philco radio to find out what was going on.”

From that moment, Cromwell became absorbed in the World War II era’s pervasive atmosphere, and remembers it today in Lubbock at age 89.

At 17, he had attempted to enlist in the military twice with his father’s blessing, but was turned down for inadequate vision – he wore glasses.

“I went ahead and finished my senior year in high school, enrolled at Pepperdine, and registered for the draft.”

By then, the war had progressed – American ships had been sunk in the Pacific – and the Selective Service had become much more approachable.

Pick a service

“After I took the draft board physical, someone with paperwork said, ‘Which do you want, Army, Navy or Marines?’ ”

He picked the Navy.

At one point, he said, he was within 100 miles of the biggest Navy base in the world that hadn’t been used for years.

“But something was going on that I didn’t know about: Eleanor Roosevelt had flown around the country, and she had looked out of her airplane and seen this big lake up in northern Idaho. She told the secretary of the Navy that it would make a good camp for the Navy because of this big lake – they could go rowboating on it.”

That was the First Lady’s inspirational concept, but something was lost in implementation:

“They sent us there for me to pack down snow in the wintertime.”

Cromwell recalls now that he was interested in amateur radio, and when offered a chance to go to the Navy’s electronics school in a curriculum called the Captain Eddy Program, he signed up.

“They sent me to Chicago to school,” he remembers.

Victory celebration

Later he was transferred to Long Island to train for the invasion of Osaka Navy Base in Japan, and was still there on May 8, 1945, when Germany signed surrender papers for the Allies’ celebrated Victory in Europe Day.

“They have that famous picture of the sailor kissing a nurse, but the photographer didn’t show all the background – I kissed a lot of nurses that night. It was jam packed until 2 or 3 in the morning.”

The celebration was quickly forgotten, though.

“Right after that, they put us on what I would call a freight train. They had the doors open and we had bunks bolted down – it was 18 boxcars. We went from Long Island to Chicago to western Kansas, and I will always remember that one, he said in referring to a community canteen project.

“We got in there at 10 o’clock in the morning, and all the ladies in town were already there to serve refreshments. They gave us a little time there to get off and get a cup of coffee and a donut, and all this fruit – oranges and apples.”

In the World War II era, necessities superseded comfort:

“We went to El Paso, and from there, to San Francisco. We had bunks underneath the race track grand stands for a few days. Then, we got on a ship and went to Hawaii.”

Majuro station

Cromwell was put on a plane and flown to Majuro, one of the islands in the Marshalls.

“The Japanese had abandoned Majuro, and had reinforced an island 700 miles west.”

A Marine flying group operated from the island to fly missions against Japan’s forces 700 miles away, and Cromwell’s unit operated the radar and electronics equipment on the remote southern end of the island, three miles from any urban area.

“We’d get in our jeep and go to town.”

While on the island, he bought the first automobile he had ever owned.

“I bought my first jeep for $20 from one of the soldiers. He had built it out of a junk yard. We were right next to a junk yard, and he would go salvage parts. But he got a brand new engine out of some box,” he said.

Majuro had at one time been occupied by Japanese troops, and at the end of the war, a few had remained behind when the others pulled out.

“The Japanese were hiding out in the jungle. I rounded up one or two, because I knew where they were hiding. We sent them home to Japan.

“They got home before I did.”

Phenomenon gone

Cromwell remembers a phenomenon that was an everyday occurrence for military personnel following the end of World War II, and which has never really returned. It was called hitchhiking.

He went all the way from the West Coast to Odessa to see his sister in Texas, then to Memphis, to stay with his parents for two weeks, and on to New York by riding with people who would pick him up along the highway. He never waited long for a ride.

“I passed up the Greyhound buses,” he remembers. “Anybody who could get a gallon of gas during that period would pick up a serviceman who was on the highway.

“It’s a lot different now,” he said.

He had discovered that World War II was a unique time in the nation’s history.

ray.westbrook@lubbockonline.com

Home › My War › A-J Remembers C. J. Solomon

A-J Remembers C. J. Solomon

Posted on April 6, 2015 by Andy Posted in My War, The One Minute Business

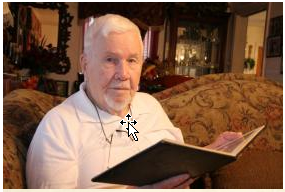

The A-J Remembers: Clifford Solomon walked for more than four months as a prisoner of war

Posted: April 5, 2015 – 8:23pm

|

Ray Westbrook / A-J Media

Clifford J. Solomon holds a portrait made of him during World War II. He served

in the Army in Europe, and was a prisoner of war for more than four months.

After Clifford J. “Bunk” Solomon was captured by German forces

in World War II, he walked for more than four months.

Solomon, now a 60-year resident of Lubbock, had grown up in Comanche County in

central Texas, and entered the 11th Airborne Division in February 1943. At 19,

he was among 57 other young men from that area who went into military service

at the same time.

He would

have gone to the Pacific sector of the war with the rest of the division except

for a high fever that kept him in the hospital for 42 days after maneuvers at

Fort Polk, Louisiana.

“I went to Mississippi to the 94th Infantry Division, and went overseas with

them. We went over on the Queen Elizabeth — the whole division — and landed in

Scotland. Then we went across England and into France. I missed D-Day by about

two months.”

Solomon’s unit spent the first week of combat at Le Havre, France.

“A lot of that I try to forget. The Germans would take their 88 and bring it

out from under the church steeple over there, and fire two or three rounds at

us and then run it back under this church steeple.”

An American commander ineffectively directed fire against the steeple with

105mm artillery, then moved two 155mm guns in to successfully topple the

structure.

“When we left there, we went right on across France to the Siegfried line, and

they had pillboxes through that,” Solomon remembers.

“We took the pillboxes that morning, and that afternoon, at dark, our company

pulled back. There were 22 of us out there on this point and the pillbox, and

they never did let us know they were going to pull back — we just sat out

there.

“And you can’t whip a tank with an M-1 rifle, so the Germans pulled across the

trenches that went into that pillbox on each side. They pointed those 88s right

down in that, and about the time they did that, our own artillery began firing

in on us — right there.”

He remembers that the artillery barrage went on for 40 minutes.

Taken prisoner

“After it was over with, the Germans got us out of the pillbox. They got us

away from the front line, and you couldn’t step without falling into a hole —

made by the artillery — that was waist deep.”

After they were taken a distance of about three miles, they were interrogated.

“Of course, when you walked in the first thing you did was to tell them your

name, rank and serial number. That’s all you had to tell them. But do you know

the first thing they asked? ‘Are you a Jew?’

“I told them, ‘No, I’m an American.’ Of course, I wouldn’t mind being a Jew,

either.”

Solomon remembers it being ironic that his grandfather was mostly of German

ancestry, a man named L.R. Auvenshine.

“They did that for two different nights. I don’t even remember the town we were

at now.”

Brief respite

But he indicates a German sergeant was cordial to the prisoners. “He asked us,

‘Would some of you boys like to help a man here who rolls cigars, would you

mind helping him do that for a couple or three days?’

“Well, I volunteered, and two more boys volunteered, and we went and rolled

cigars.”

For a short time, it was a dichotomy of war, a kind of interlude from danger.

The American soldiers, held by the enemy, were allowed to help a German

civilian in a business unrelated to World War II.

“They had that in an old school house there. We carried a roll of cigars that

we had rolled back to the boys that evening. And that German man that we were

working for, his wife would have us pull our uniforms off and put his clothes

on, and she would wash and press our uniforms for us.”

He felt he wouldn’t have been treated better had they been his own mother and

father.

Post card from home?

“After he found out I was from Texas, he said, ‘I’ve got something I want to

show you.’ So, he went in the house and brought back a postcard and handed it

to me. He said, ‘Do you happen to know where this is in Texas?’

“It was Brownwood, Texas. I lived 25 miles from there. The old man himself had

been a prisoner of war of the Americans in 1918. And he had a son who was a

prisoner of the Americans — and he was at Brownwood.

“He told me, ‘My son doesn’t even want to come home.’”

The post card had come from his son who was being held in Brownwood.

‘Walked all the time’

When the civil service was over, Solomon and the others began walking, and

began to be in need of both food and rest.

“We walked all the time I was a prisoner.”

Germany’s dictator, Adolph Hitler, apparently had ordered all prisoners killed,

so Solomon and several other American prisoners were marched across Germany to

within 40 miles of Austria instead. In a kind of incongruous resistance to

Hitler’s maniacal violence against human beings, the German guards kept the

prisoners moving on the road instead of turning them in to a prison camp.

“I never was in a prison camp. Hitler had given orders to kill all prisoners,

so that’s why they kept us walking all the time.”

Yet there was violence, contempt and similarities to Japan’s infamous Bataan

death march:

“You could not fall out to help a buddy if he got so tired and fell out beside

the road — you got shot.”

He remembers, “There were lots of towns that we walked through — I imagine why

they did that was because they were mad about what was going on — but they

would try to spit on us. And the night when they captured us they would try to

hit us over the head with rifle butts.

“Of course, I know we had lots of mean soldiers — when you got over there, you

got hard-hearted, you nearly had to to stand it. But I’ve seen some things that

I don’t even want to think about.”

Not much to eat

He recalls of the forced hike across Germany, “Once in a while, while I was a

prisoner, they would give us what I called about a No. 3 can for 20 men. So,

you can imagine how much meat there was. Sometimes we would go three or four

days without a bite to eat. I’ve seen lots of fights, just like the Russians

fighting over snails and the apple trees.

“It was really hard. I was able to stand up. I kept a’going, I kept a’going. It

was necessary.”

Solomon lost 51 pounds during the march.

“Gen. George Patton liberated me,” Solomon said, and added not one word of

criticism of the controversial general.

“That morning that big tank rolled up there with that big white star — I tell

you what, that looked great. The German guards had left. I don’t know what

happened to them. During the night they took off.

“It was the 13th Armored Division.”

He remembers, “They set up a tent out there, and you could go out and eat 24

hours a day if you wanted to. Any time you got hungry, you could go eat.”

Lingering effects

When he was home after the war ended, he remembers that the effects of

starvation had reduced the amount he could eat.

“I would sit down at the table at my mother-in-law’s house, and I would eat two

or three bites, and I was up. That’s all I could go. She thought it was

something wrong with her cooking, and I said, ‘Mother, don’t worry about that —

I can’t eat any more than that, I’m full already.’”

Solomon doesn’t hold animosity for the German people.

“There are lots of great German people over there, because they didn’t want

that war any more than we did. It was Hitler,” he said.

“Thank the good Lord; he’s paying for that now.”

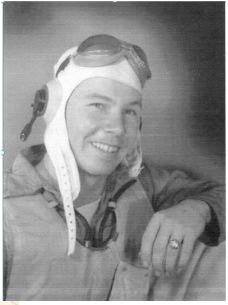

The A-J Remembers: Andy Winnegar fought Pacific war in the sky

Winnegar served as gunner, bombardier, surveillance photographer aboard carrier-based plane

Posted: March 15, 2015 – 3:52pm | Updated: March 16, 2015 – 12:18am

Ray

Westbrook / A-J Media

Andy

Winnegar has a squadron book in his home that has the pictures and names of the

men he served with while helping to take Saipan in the Pacific theater of World

War II.

Andy Winnegar is shown wearing a cotton-cloth helmet that he wore in combat in the hot Pacific sector of World War II. It is similar to one worn when he was wounded as a shell passed through his plane.

By Ray Westbrook

A-J MEDIA

While families were sleeping uneasily at home, sons of the nation were

struggling daily in the tangible portion of World War II.

According to notes kept by Navy veteran Andy Winnegar, now a resident of

Lubbock, the day-to-day combat took soldiers many times to the edge of — and

sometimes beyond — life.

Winnegar’s father, a World War I veteran, had died at that time, but his mother

and sister waited at home.

“We never thought of losing the war — that was never a thought. We thought we

might die, in fact our slogan was ‘back alive in 45.’”

Winnegar served as gunner, bombardier and surveillance photographer aboard a

carrier-based plane that could carry eight rockets, 12 100-pound anti-personnel

bombs, four 500-pound bombs or four depth charges. It was launched by catapult.

His role in the invasion of Saipan in the Mariana Islands was that of

low-altitude flying in precarious positions: “We were flying above the naval

gunfire, under the artillery and in the traffic of other planes.”

D-Day on Saipan was June 15, 1944, which had been eclipsed by the June 6 D-Day

invasion of Normandy. Yet, it was a costly, three-week battle for Marines of

the 2nd and 4th Divisions, and the 27th Infantry Division.

First waves

According to Winnegar, who was flying above the first waves going ashore, it

was primarily the men on the ground who were dying. “We lost 2,000 men the

first day.”

By the end of the Saipan battle, almost 3,500 Americans had died, and as many

as 10,000 were wounded. The Japanese losses amounted to about 24,000 killed and

900 taken prisoner.

The island offered a landing strip for planes, and it was near Tinian, which at

that time had not been taken but would ultimately be the launching air strip

for planes carrying the atomic bombs that brought World War II to an end.

Winnegar had enlisted in the Navy at 17 in July 1942, but with abilities in

education, the military apparently was investing much of his time in schools.

He studied radio and radar at Northwestern University, Evanston, Ill., and

Naval Air Technical Training Center in Memphis, Tenn., and toward the end of

the war, was enrolled in flight training.

He remembers of the Saipan invasion, “We carried a Marine observer, Capt. Grady

Gatlin. We were directing both naval gunfire, and after they established the

beachhead, then Marine artillery.”

Hazardous duty

Winnegar, who volunteered for the hazardous duty, was in an area of the plane called a tunnel, located immediately behind the bomb bay.

“We were flying from 500 to 1,000 feet altitude when observing at Saipan — we had to be low enough to see what was going on — and we were hit by what they said was a 37 mm. I really think it was actually an 88.”

Whatever the size of the shell, it was armed. “I was taking pictures with a K-20 camera, a big camera. It had a lever on the side, and as I leaned back to cock it, this shell came through and I could smell the powder, which meant the fuse was burning in it. But it came through the door and went out the bottom of the plane.

Winnegar was wounded indirectly by the shell. “I was wearing a cotton (cloth) helmet with goggles, and it busted the lens on the top and cut my head — not the actual shell, but pieces from the airplane. Gatlin came down out of the turret, grabbed the mike, and told the pilot that I was hit. He called Air Command and asked to be relieved from the station, which they did pretty shortly. He put a big compress on my head.

“There was a little blood in my eye, and I thought it was bad. My head was numb and I was having trouble hearing.”

He saw the pamphlets that had been planned for the civilian population telling them that the Americans weren’t fighting them, plastered all over the tunnel.

“Shortly after that, I got enough nerve to reach up there and press — and there wasn’t a hole in my head! It was just the skin that had been cut. When I found out there wasn’t a hole in my head, I got the mike and said, ‘Hey, I’m okay. I can finish the flight.’ Gatlin said, ‘He doesn’t know what he’s talking about.’ Then the pilot told us both to shut up.”

When they landed on the carrier, the flight surgeon and pharmacist’s mate were waiting on deck with a stretcher, but Winnegar declined to go to sick bay and went instead to wait debriefing. Combat journal

Winnegar kept a journal of his time in combat that reveals how perpetually the men contended with the details of war:

“June 16, 1944: D-Day plus one. Two observation missions today. We cornered a couple of Jap tanks and made rocket and strafing runs on them. Some near misses and one hit put one of them out of action … we were fired on while strafing some Jap positions but got nothing the metal smiths can’t repair overnight … Two trucks coming down the road opened up on us with machine guns, we climbed up to 3,000 feet, circled and came in behind them at near ground level … a little later, Gatlin spotted what looked like an anti-tank gun in an earthen embankment with a number of troops around it and we used up our remaining ammunition.

“June 17, 1944: Today we have the last observation mission of the day. The plane that we are relieving is shot up so badly they are forced to land on the little strip at Chalan Kanoa which the 2nd Division took on D-Day.

“We spotted Jap anti-tank guns cleverly set up in front of a rise where a tank approaching it would expose its belly before coming over the incline. One of our tanks was burning and another was approaching. We asked for permission to attack with rockets and bombs and were refused. Owens strafed the position anyway and shortly after they gave us permission to attack with rockets.

“We still had our load of bombs and needed to unload before we landed on the ship, so we went back to the guys on Tinian that had nicked our elevator and attempted to drop on them, but neither Owens nor I could get the bombs to release.

“A group of Jap bombers were headed for our force and we needed to get back. We landed safely on the ship, and a few minutes later we were under attack.”Enemy approaching And more war: “Shipmate information. ‘At 1800 we picked up bogey at 124 miles, the raid split into three groups. The ship went into general quarters. We tracked raids coming in, sent our fighters to intercept, made some interceptions at 30 miles. Pilot reported 20 bombers, 15 fighters in one group … main group that broke through attacked west side. About 8 to 12 torpedo and dive bombers came at us on the east side. About four to six different times we opened fire. Our ship’s anti-aircraft fire downed one torpedo plane and one dive bomber.

“‘The Fanshaw Bay got a 500-pound bomb hit on the aft elevator. It exploded in the elevator pit. Split seams and they took on some water. Killed 13 outright and two died next day. She started back for Pearl. A destroyer and tanker were hit a few miles from us. In bringing our planes on board, two fighters went over the side. Another fighter hopped over the barrier and crashed into five other planes and started a fire. Fire was put out. One man was reported knocked overboard with a plane. Another man was hit and severely injured. He died before morning.’”

Winnegar entered flight school after Tinian was taken, then with enough points to leave the Navy and an affinity for planes; he joined the National Air Shows for aerobatics flying.

Honor Flights

He kept his memories of military service, though, and went on one of the South

Plains Honor Flights. That project, headed by Lou Ortiz and publicized by Larry

Williams, was even more than Winnegar thought it would be.

“I was on the 2012 Honor Flight and it was one of the greatest experiences of

my life — three days of action-packed bus trips that brought back all the old

memories of companionship. I hope all of our South Plains veterans will get an

opportunity to take the trip. My roommate was the only ex-POW on the trip, C.J.

“Bunk” Solomon, and we have been in almost weekly contact since the trip.”

He has a home in Lubbock with his wife, Dolores.

But Winnegar misses the particularly united United States of World War II.

“The nation was united in World War II. It has never been the same again,” he

said.

“It would be wonderful if we could get that feeling back.” -30-